CHAPTER 7: Backlog and Requirements Management

The Competitive Edge for Modern Project Managers

7.1 Product Backlog – Characteristics, Prioritization, and Continuous Refinement

Introduction to the Product Backlog

In Agile projects, the product backlog is the single source of truth for what the team will build. It is a prioritized list of everything that might be needed in the product. Unlike a traditional requirements document, it is not fixed at the start. Instead, it evolves as new ideas, insights, and customer feedback emerge. Think of it as a living document that guides the team step by step toward delivering value.

What the Product Backlog Contains

The product backlog includes features, functions, enhancements, and fixes. Each item, sometimes called a backlog item, represents a piece of work that contributes to the overall product. Items are written in plain, customer-friendly language rather than technical jargon. They range from large ideas, such as capabilities or epics, to smaller, actionable items like user stories. The goal is to capture what delivers value for customers and the business.

Characteristics of a Good Backlog

A well-managed backlog has a few key characteristics.

- It is prioritized, so the most valuable items are at the top.

- It is refined, meaning the top items are detailed enough for the team to work on soon.

- It is estimated, giving the team a sense of effort required.

- It is emergent, always open to change as new insights arise.

Together, these traits make the backlog a flexible yet reliable planning tool for the entire Scrum team.

Prioritization and Value Delivery

Not all backlog items are equal. Some deliver high customer value, while others are less urgent. Prioritization ensures that the team always works on what matters most. The product owner, in collaboration with stakeholders, is responsible for ordering the backlog. Factors influencing priority include customer value, risk, dependencies, and alignment with business strategy. By continuously reviewing priorities, the team ensures they maximize value with each sprint.

Continuous Refinement

Refinement is the ongoing activity of keeping the backlog relevant and actionable. Teams hold refinement sessions, often once per sprint, where they clarify details, split large items, and adjust estimates. This practice prevents surprises during sprint planning. It also ensures that the backlog remains a ready pipeline of work. Continuous refinement reduces uncertainty and helps the team stay aligned with evolving business needs.

Benefits of a Well-Managed Backlog

A well-structured backlog provides transparency for everyone involved. Stakeholders can see what is coming and when. Teams can plan with greater confidence, knowing that priorities are clear. It also fosters adaptability, allowing the product to evolve with customer feedback or market shifts. By focusing on the most valuable items first, the backlog becomes a powerful tool for delivering customer satisfaction and business results.

7.2 Backlog Prioritization – Tools, Techniques, and Examples

Introduction to Backlog Prioritization

Backlog prioritization is more than sorting tasks in order. It is a structured decision-making process that ensures teams always focus on what delivers the highest value. With many possible features and limited time, prioritization helps product owners and teams make trade-offs. This explores two powerful prioritization techniques in depth: the MoSCoW method and Weighted Shortest Job First, also called WSJF.

The MoSCoW Method

The MoSCoW technique is a simple but effective way to categorize backlog items. It divides work into four categories: Must Have, Should Have, Could Have, and Won’t Have at this time. This method provides clarity, especially in projects with diverse stakeholders. Everyone can see which features are essential and which are optional.

MoSCoW Example

Imagine a new mobile banking app. The backlog includes features like viewing account balances, money transfers, bill payments, fingerprint login, and dark mode for the interface. Using MoSCoW, the team may classify viewing account balances and money transfers as Must Have items. These are core functions without which the app has no value. Bill payments might be a Should Have, since many users expect it but it is not critical at launch. Fingerprint login could be a Could Have, as it adds convenience but is not essential in the first release. Dark mode may be labeled as Won’t Have for now, because it can wait until after launch. By applying MoSCoW, the product owner sets clear expectations about what will be delivered first.

Weighted Shortest Job First (WSJF)

WSJF is a more analytical technique that combines value and cost. It comes from Lean Portfolio Management and is widely used in scaled Agile environments. The formula is simple: WSJF equals the Cost of Delay divided by the job size. Cost of Delay represents the value lost by delaying an item. Job size is the effort needed to complete it. Items with the highest WSJF score rise to the top of the backlog, because they deliver the most value in the shortest time.

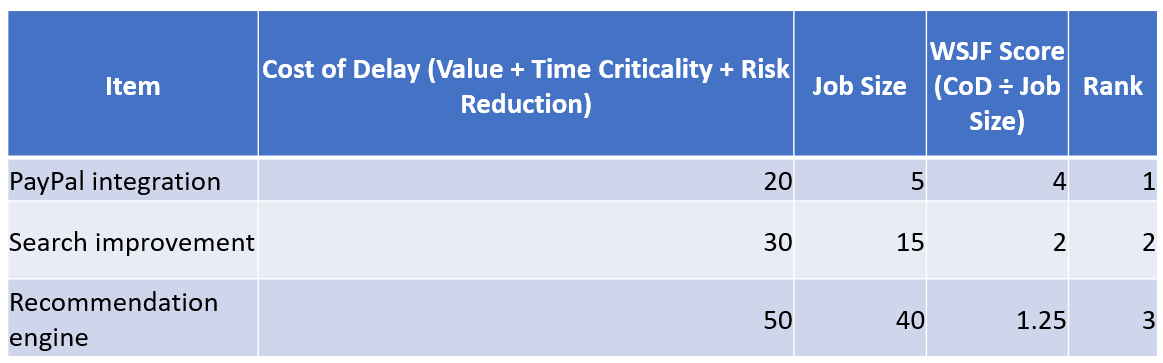

WSJF Example

Consider an e-commerce platform deciding between three backlog items: adding PayPal as a payment option, improving the search algorithm, or creating a product recommendation engine. The team assigns business value, time criticality, and risk reduction or opportunity enablement to calculate Cost of Delay. Suppose PayPal integration scores 20, search improvement scores 30, and recommendations score 50. Then the team estimates job size: PayPal integration requires 5 units of effort, search improvement 15, and recommendations 40. Dividing Cost of Delay by job size, PayPal has a WSJF score of 4, search improvement 2, and recommendations 1.25. This means PayPal integration should be done first, even though recommendations have higher value, because they require much more effort. WSJF ensures the team invests its limited capacity where it pays off fastest.

Comparing the Two Approaches

The MoSCoW method is best when you need a quick, qualitative decision that stakeholders can understand easily. It is especially useful in smaller projects or early product discussions. WSJF is stronger when you need to balance business value with effort and when trade-offs are complex. It brings more data into the decision and prevents teams from chasing high-value features that are too expensive to build early. Many organizations use both: MoSCoW for initial categorization and WSJF for fine-grained prioritization.

Conclusion

Prioritization is not about building everything. It is about making smart choices with limited time and resources. Techniques like MoSCoW and WSJF give structure to these choices. MoSCoW provides clear categories, while WSJF balances value against cost. By applying these methods with real backlog items, Agile teams can deliver value quickly, manage stakeholder expectations, and avoid wasting effort.

Read more on our blog:

The Project Leader’s Superpower: Prioritization and Decision-Making Tools That Actually Work

Weighted Shortest Job First (WSJF): Your Agile Ally for Smarter Prioritization

7.3 Backlog Hierarchy – Capabilities, Features, and User Stories

Introduction to Backlog Hierarchy

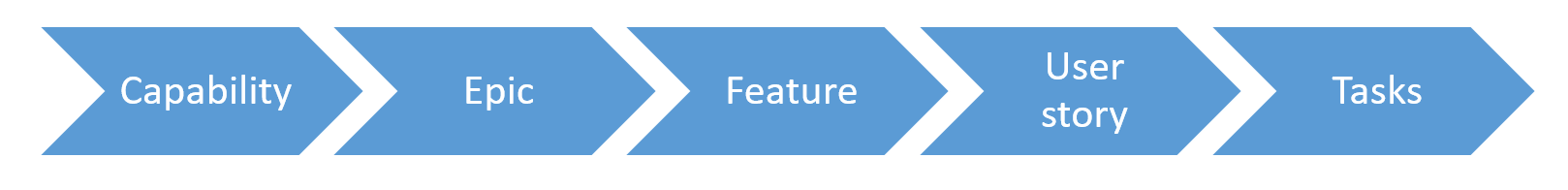

Agile backlogs contain large ideas, mid-sized functions, and detailed work items. To keep them organized, teams use a hierarchy. This hierarchy ensures that broad business goals connect directly to the work delivered in each sprint. The main levels are capabilities, epics, features, and user stories. Each level plays a role in linking strategy with execution.

Capabilities – The Big Picture

Capabilities sit at the top of the hierarchy. They describe what the organization wants the product to achieve at a business level. Capabilities are too large to deliver in one release. For example, in an online learning platform, a capability might be “Enable personalized learning experiences.” This goal provides direction and helps ensure all work aligns with strategic objectives.

Epics – Large Units of Work

Epics bridge the gap between broad capabilities and more detailed features. An epic is a large body of work that may take multiple sprints or even several releases to complete. Epics give structure to the backlog by grouping related features together. For instance, under the capability of personalized learning, one epic might be “Implement adaptive assessments.” Another epic could be “Develop learner progress insights.” These epics provide a manageable way to organize large themes of work.

Features – Connecting Epics to Value

Features are narrower than epics and describe specific product functions that deliver value to the user. While still larger than a single sprint, features can usually be delivered within a release. For example, the epic “Implement adaptive assessments” might include features such as “Adaptive quiz engine” or “Difficulty adjustment logic.” Features move the product closer to achieving the epic, which in turn contributes to the larger capability.

User Stories – The Smallest Workable Units

User stories represent the most detailed level in the backlog. They are small, testable units of work written from the end user’s perspective. A story should be small enough to complete within one sprint. For example, under the feature “Adaptive quiz engine,” a story might be “As a student, I want to see more challenging questions after I answer correctly, so that I continue to improve.” Stories make sure that every backlog item is user-focused and delivers clear value.

How the Levels Fit Together

Capabilities, epics, features, and user stories form a connected chain. Capabilities set the high-level business goals. Epics break those goals into large, organized themes. Features then describe specific functions within each epic. Finally, user stories provide actionable items for the team to deliver in a sprint. This structure ensures that even the smallest story ties back to business strategy and customer value.

Capabilities vs. Epics

Capabilities and epics are not the same, although they are closely related. A capability describes a high-level business outcome, usually tied to strategic goals. It answers the question, “What broad ability should the product provide?” Epics, on the other hand, are large bodies of work that sit under a capability. They are more concrete and can be broken down into features. In simple terms, a capability is the “why,” while an epic is a large “what” that helps achieve it.

For example, in a healthcare system, a capability might be “Enable secure digital patient records.” Within this capability, one epic could be “Implement patient data encryption.” Another epic might be “Develop role-based access control.” Each epic contributes to fulfilling the larger capability but remains too large to deliver in a single sprint.

Benefits of the Hierarchy

Using a backlog hierarchy brings clarity and alignment. Leaders can see how strategy flows into delivery. Product owners can organize the backlog without losing sight of big goals. Teams can focus on stories while knowing how they support larger epics and capabilities. Stakeholders also find it easier to discuss priorities, because the hierarchy makes relationships between different levels of work visible.

Conclusion

Backlog hierarchy is more than an organizational tool. It is a way to connect vision to execution. Capabilities express strategic goals. Epics organize large themes of work. Features define valuable product functions. Stories capture specific user needs. Together, they help Agile teams deliver value step by step, while staying aligned with the bigger picture.

7.4 Writing Effective User Stories

Introduction to User Stories

User stories are one of the most widely used tools in Agile. They capture requirements in a simple, user-centered format. Instead of technical specifications, a user story describes what the user needs and why. The purpose is to focus on value, not just tasks. Well-written stories help teams understand the customer perspective and deliver solutions that matter.

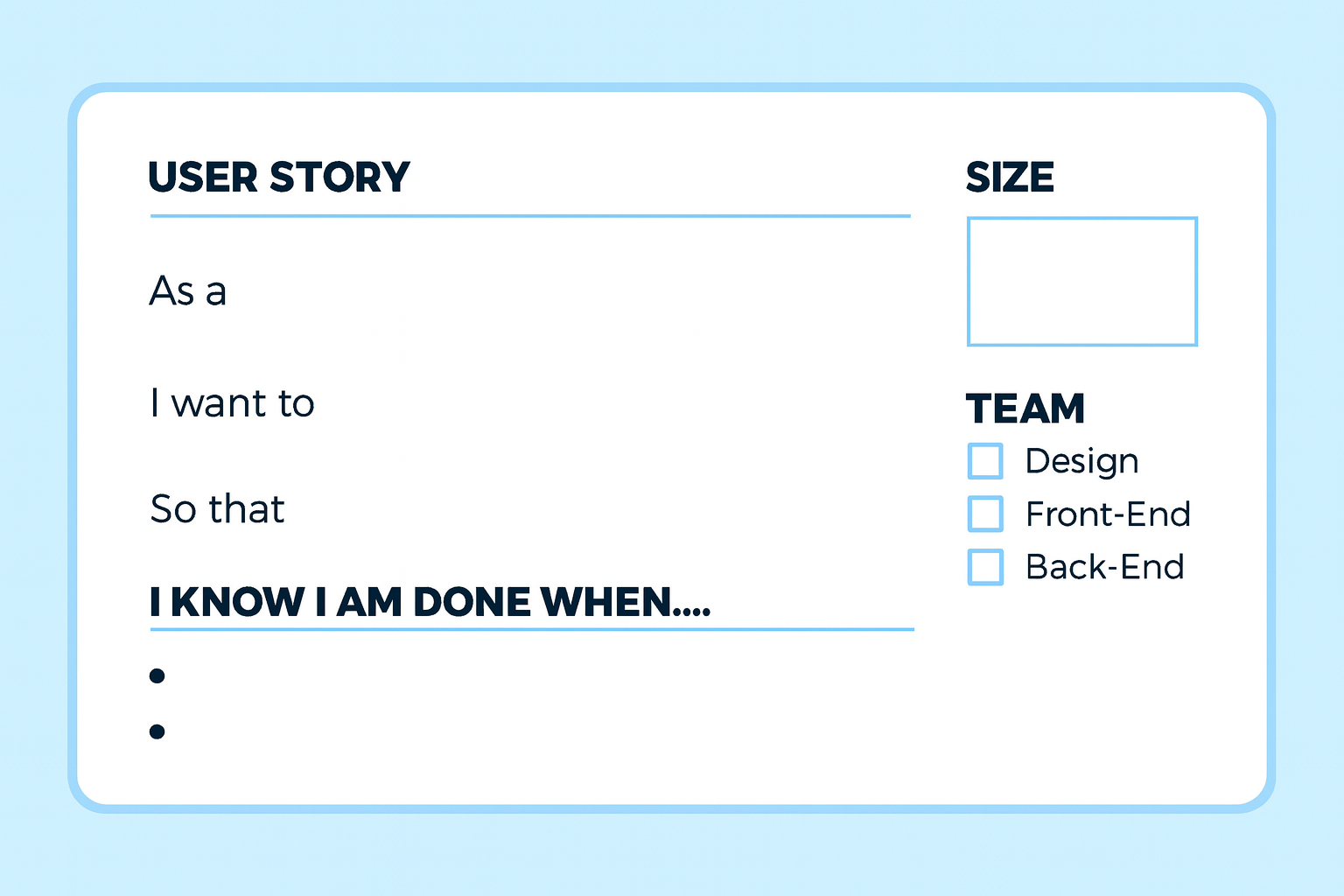

The Standard User Story Format

The most common format for user stories is: “As a [user role], I want [goal], so that [reason].” This structure ensures three things. It identifies who the user is, what they want to achieve, and why it is important. This keeps stories customer-focused instead of solution-focused. For example: “As a shopper, I want to save my items in a cart, so that I can purchase them later.”

Characteristics of a Good User Story

Good user stories share a few qualities.

- Independent, so they can be delivered separately.

- Negotiable, meaning the details can be discussed.

- Valuable, providing benefit to the user.

- Estimable, allowing the team to size the effort.

- Small enough to complete within a sprint.

- Testable, with clear acceptance criteria.

Together, these qualities are known as the INVEST model.

Examples of Clear and Poor Stories

A clear user story might be: “As a student, I want to reset my password, so that I can access my account if I forget it.” A poor story would be: “Build password reset feature.” The second example is task-focused, not user-focused. It lacks a user role, a reason, and a clear outcome. Writing stories in the right format makes them easier for the team to understand and test.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Teams sometimes make mistakes when writing user stories. One mistake is making them too large. For example, “As a student, I want to manage all course features, so that I can study better.” This is too broad and should be split into smaller stories. Another mistake is writing stories as technical tasks, such as “Create database schema.” While technical work is important, it should be linked to a story that explains its user value.

Refining User Stories

Stories are not complete when first written. They are refined through collaboration between the product owner, team members, and stakeholders. During backlog refinement sessions, the team clarifies details, adds acceptance criteria, and breaks large stories into smaller ones. This process ensures that stories are ready for sprint planning. Refinement keeps stories aligned with business value and makes them actionable for the team.

Conclusion

Effective user stories connect the team’s work directly to user needs. By using the standard format, applying the INVEST model, and avoiding common mistakes, teams write stories that are clear, valuable, and testable. Strong user stories create focus, reduce misunderstandings, and help Agile teams deliver features that truly serve their customers.

7.5 What Developers Do with User Stories

Introduction to Working with User Stories

Writing good user stories is only the beginning. The real value comes when the development team takes ownership of those stories. In Scrum, the team does not wait for tasks to be assigned. Instead, members self-organize to select, break down, and deliver the stories. This keeps accountability with the team and ensures that the product owner and Scrum master do not micromanage daily work.

Taking Stories from the Board

During sprint planning, the team commits to a set of user stories from the product backlog. These stories move into the sprint backlog. Once the sprint begins, individual team members take stories from the board. This is not directed by the Scrum master or product owner. Instead, team members pull work themselves, creating a sense of ownership and shared responsibility.

Breaking Stories into Tasks

User stories describe what needs to be built from the user’s perspective. To deliver a story, the team must figure out the detailed steps. Developers break the story down into smaller technical tasks. For example, a story about password reset might become tasks such as design the reset form, create backend logic, send confirmation email, and test functionality. These tasks are added to the sprint board to track daily progress.

Who Manages the Tasks

It is important to clarify that the Scrum master does not assign or manage tasks. The Scrum master’s role is to facilitate the Scrum process, remove impediments, and coach the team in Agile practices. Task management belongs entirely to the developers. They decide how to divide work, who takes which tasks, and how to collaborate. This empowers the team to self-organize and continuously improve how they deliver value.

Collaboration and Swarming

Agile teams often work together on a single story rather than splitting work by specialty. This practice, sometimes called swarming, helps deliver stories faster and reduces handoffs. Instead of one developer owning a story alone, multiple members may collaborate on tasks until the story is complete. This creates shared understanding and higher quality outcomes.

Benefits of Team Ownership

When developers own the process of breaking down and managing tasks, several benefits appear. The team builds a stronger sense of accountability. Bottlenecks are reduced, because no single person controls the flow of work. Transparency improves, since all tasks are visible on the board. Most importantly, the product owner and Scrum master can focus on their responsibilities while the team manages daily work.

Conclusion

User stories set the stage, but it is the development team that brings them to life. They pull stories, break them into tasks, and self-organize to deliver value. The Scrum master supports the process but does not manage tasks. By keeping task ownership with the team, Scrum fosters empowerment, collaboration, and continuous delivery of high-quality work.

7.6 User Stories and Acceptance Criteria

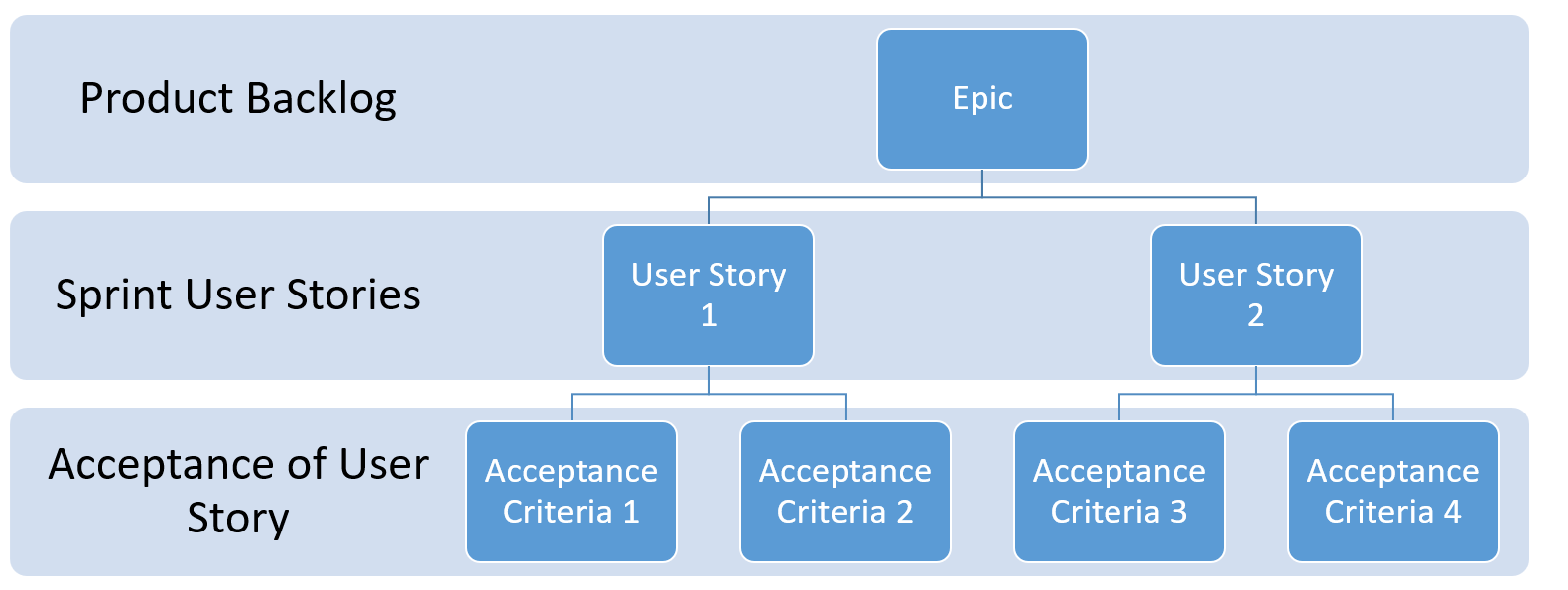

Introduction to Acceptance Criteria

User stories describe what the user wants and why. However, they do not specify exactly when the story is considered finished. That is where acceptance criteria come in. Acceptance criteria are conditions that must be met for a story to be complete. They transform a general statement into a testable requirement that guides both development and validation.

Purpose of Acceptance Criteria

Acceptance criteria serve multiple purposes. They create shared understanding between the product owner, developers, and testers. They reduce ambiguity by clarifying exactly what is expected. They also provide a clear basis for testing. If the acceptance criteria are met, the story can be marked as done. If not, the team knows more work is required.

How to Write Acceptance Criteria

Acceptance criteria should be simple, clear, and measurable. They are often written as short statements that define behavior. A common format is the Given-When-Then structure. “Given” describes the context, “When” describes the action, and “Then” states the expected outcome. This approach links user actions to system responses in a structured way.

Example of Acceptance Criteria

Take the story: “As a student, I want to reset my password, so that I can access my account if I forget it.” Possible acceptance criteria could be:

- Given I am on the login page, when I click “Forgot Password,” then I see a reset form.

- Given I submit my email, when the system processes it, then I receive a reset link.

- Given I click the reset link, when I create a new password, then I can log in with it.

These criteria make the story testable and prevent misunderstandings.

Who Defines Acceptance Criteria

The product owner is responsible for ensuring that acceptance criteria exist for backlog items. However, criteria are often refined collaboratively. Developers and testers may suggest adjustments to make them practical and testable. This collaboration ensures that acceptance criteria are realistic and achievable within the sprint.

Acceptance Criteria vs. Definition of Done

It is important not to confuse acceptance criteria with the Definition of Done. Acceptance criteria apply to individual stories. They define what makes that specific story complete. The Definition of Done, on the other hand, is a team-wide agreement that applies to all work. It might include standards for coding, testing, or documentation. Together, acceptance criteria and the Definition of Done ensure both story-level and team-level quality.

Benefits of Strong Acceptance Criteria

Strong acceptance criteria improve quality and reduce rework. They make stories more predictable, because everyone knows what success looks like. They also speed up testing, since testers can use the criteria as a checklist. Most importantly, they build trust with stakeholders by showing that the product behaves exactly as expected.

Conclusion

User stories capture intent, but acceptance criteria bring precision. By writing clear, measurable conditions, teams transform ideas into testable outcomes. This practice strengthens collaboration, reduces confusion, and ensures that delivered stories truly meet user needs.

7.7 Epics, Themes, and Nonfunctional Requirements

Introduction to Large Backlog Items

Not all backlog items are small and ready to deliver. Some are large ideas that span multiple sprints or even releases. Agile teams use epics and themes to organize these bigger items. Alongside them, nonfunctional requirements describe essential qualities that every feature must meet, such as security or performance. Together, these elements give structure to the backlog and ensure that both business goals and product quality are addressed.

Epics in Agile

An epic is a large body of work that cannot be completed in a single sprint. Epics often represent significant functionality or a broad objective. They act as containers for related features and stories. For example, in an online store, an epic might be “Provide secure payment options.” Within that epic, features could include credit card checkout, PayPal integration, and fraud detection. By grouping related work, epics provide structure without losing sight of user value.

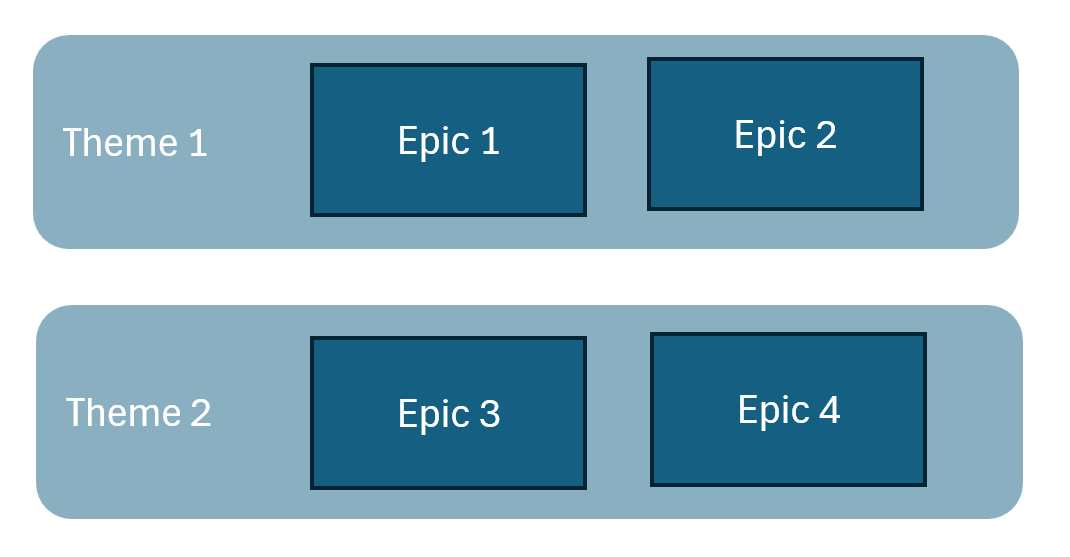

The Role of Themes

Themes are broader than epics. A theme is a collection of related epics, features, or stories that share a common goal. Themes help teams track progress across different areas of the product. For example, in the same online store, a theme might be “Improve customer trust.” That theme could include epics on secure payment, transparent return policies, and privacy controls. Themes are useful for aligning the backlog with strategic business priorities.

Nonfunctional Requirements

While epics and themes focus on functionality, nonfunctional requirements describe how the system should perform. These requirements cover areas such as security, reliability, performance, and usability. They apply across many backlog items and often become acceptance criteria. For example, a nonfunctional requirement might state that “The system must support 10,000 users simultaneously without performance loss.” These requirements ensure that the product is not only useful but also dependable.

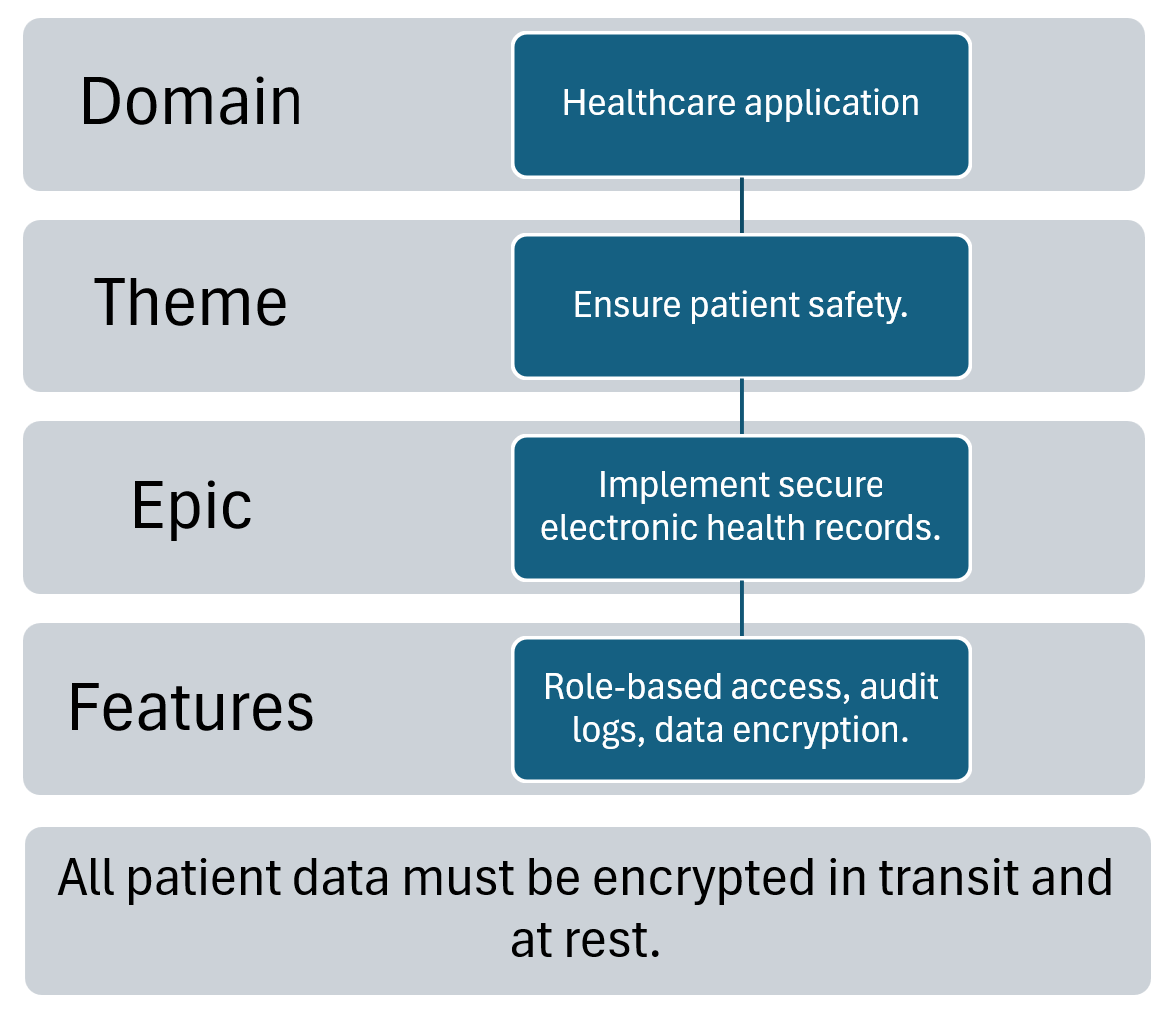

Examples of Epics, Themes, and Nonfunctional Requirements

Consider a healthcare application. A theme might be “Ensure patient safety.” Within that theme, one epic could be “Implement secure electronic health records.” Features under that epic might include role-based access, audit logs, and data encryption. Alongside these, a nonfunctional requirement could specify that “All patient data must be encrypted in transit and at rest.” This example shows how functional and nonfunctional needs work together to deliver value.

How They Fit Together

Themes, epics, and nonfunctional requirements ensure that the backlog reflects both strategic direction and product quality. Themes keep the backlog aligned with organizational goals. Epics group related features into meaningful chunks. Nonfunctional requirements act as quality standards that guide design and development across the entire product. When combined, they give the backlog balance between value, scope, and quality.

Conclusion

A strong backlog includes more than stories. It includes themes to align with strategy, epics to structure large bodies of work, and nonfunctional requirements to guarantee quality. By managing all three, Agile teams ensure they are not just building features, but building the right product in the right way.

7.8 Understanding the Backlog Hierarchy Clearly

Introduction to Backlog Hierarchy

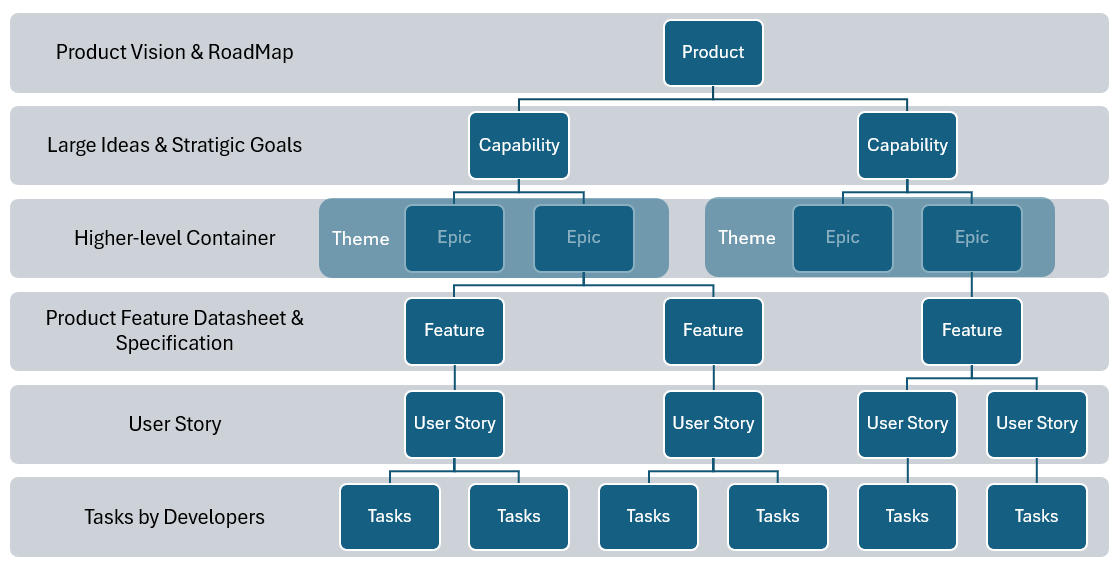

Are you lost yet ? All these terms like epics, themes, capabilities, features, and user stories, the hierarchy can feel confusing. Different organizations also use slightly different labels and structures. That is why it is important to step back and see the bigger picture. The main point is not to memorize every term, but to understand that backlog items form a hierarchy. Large ideas are broken into smaller pieces until they are ready for the team to build.

Different Organizational Approaches

In some companies, you may hear the word capability at the top of the hierarchy. In others, you may hear epic used in the same way. Some organizations use themes to group epics by business objective. The details of the hierarchy can vary, and that is normal. What matters most is that there is a structured way to move from a broad vision down to deliverable work items. Do not get stuck on the labels—focus on the flow.

Understanding the Backlog Hierarchy

Here is one example of how the backlog hierarchy can flow. You begin with the product vision, then identify capabilities that describe what the product should achieve. From capabilities, you define epics, which can be grouped under themes if needed. Epics are broken down into features, features into user stories, and user stories into tasks that developers complete during a sprint. Remember, this structure is flexible. You do not need to follow it exactly. Adapt it to fit the needs of your project and your organization.

The Scrum Perspective

In pure Scrum, the official backlog item is the product backlog item, often written as a user story. Scrum does not formally define epics, capabilities, or themes. However, many teams find these larger structures helpful for organizing work. Epics or capabilities serve as containers for many user stories. They are not separate artifacts in Scrum but can be used as practical tools to manage scale and complexity.

The Practical Flow from Idea to Task

The most important takeaway is the natural flow of work. You begin with a big idea, which might be expressed as a capability or an epic. From there, you identify features, which are significant product functions that add user value. Each feature is then broken into user stories, which describe specific needs in a simple format. Finally, during sprint planning, the developers take each story and break it into technical tasks. This flow ensures that the smallest task connects back to the original idea.

What to Remember

Do not get lost in the terminology. Remember the purpose of the hierarchy: start big and grow with ideas, then refine step by step into work that can be completed in a sprint. In Scrum, the focus is always on user stories, but many organizations use capabilities or epics above them for clarity. The hierarchy is only a tool, not a rule. What matters is that your backlog connects vision to delivery, and that every task done by developers links back to user value.

Conclusion

The backlog hierarchy is about flow, not labels. Different companies adapt it in different ways. Scrum keeps it simple by focusing on the product backlog and user stories, while many organizations add epics, capabilities, or themes to manage scale. The key point is that you start with an idea, refine it into features, break it into stories, and then into tasks. This way, you always maintain alignment between strategy and the daily work of the team.

7.9 Backlog Refinement Techniques – Workshops, Story Splitting, and Story Mapping

Introduction to Backlog Refinement

Backlog refinement is the ongoing process of reviewing and improving backlog items. It ensures that stories are clear, prioritized, and ready for development. Refinement is not a one-time event. It is a continuous activity that keeps the backlog healthy and aligned with business goals. This covers three practical refinement techniques: workshops, story splitting, and story mapping.

Backlog Refinement Workshops

Workshops are structured sessions where the product owner, developers, and sometimes stakeholders collaborate to refine backlog items. These meetings are shorter and less formal than sprint planning. The team reviews items, clarifies details, estimates effort, and reorders priorities. Workshops prevent surprises in sprint planning and give everyone a chance to contribute. They also strengthen shared understanding, because requirements are discussed openly instead of being handed down.

Story Splitting

Sometimes user stories are written too large to complete in a single sprint. Story splitting is the technique of breaking a big story into smaller, more manageable pieces. Splitting should not remove value; each smaller story must still deliver something useful. For example, the story “As a student, I want to track my learning progress” could be split into “Track completed lessons,” “Track quiz results,” and “View progress dashboard.” Splitting makes work estimable and achievable, while still moving toward the larger goal.

Story Splitting Patterns

There are many ways to split stories.

- By workflow step.

- By data type, such as supporting one file format before adding others.

- By business rule, such as implementing the simplest rule first and more complex ones later.

- By user role, for example creating functionality for students first, then teachers.

These patterns ensure that splitting results in valuable, testable stories rather than technical fragments.

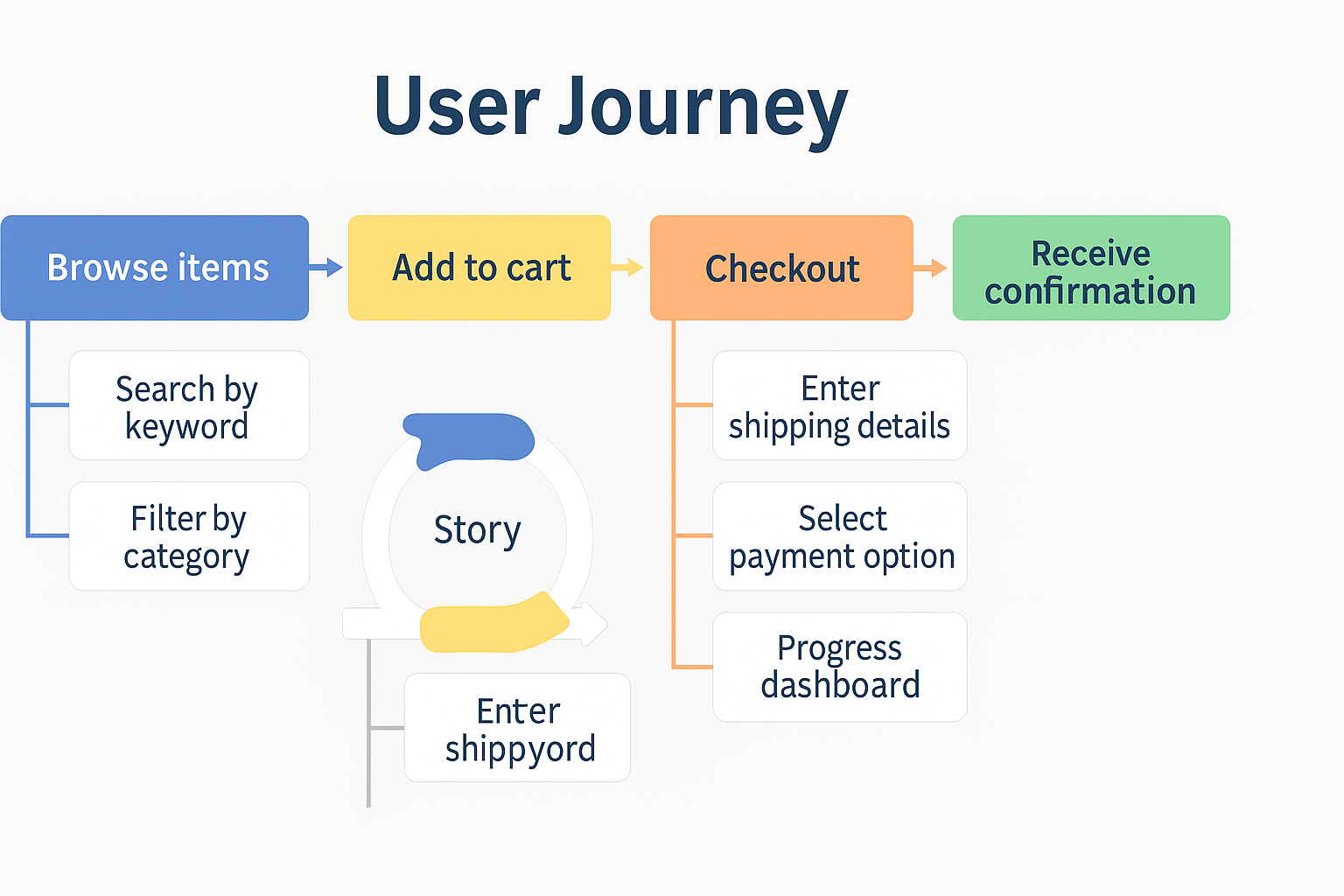

Story Mapping

Story mapping is a visual technique to see the big picture of the product. It starts with a user journey, showing the steps a user takes to achieve a goal. Under each step, the team places related user stories. This creates a map that shows how stories connect to real user activities. Story mapping helps identify missing stories, spot dependencies, and prioritize what is most important. It also supports release planning by highlighting the smallest set of stories needed for a usable product.

Example of Story Mapping

Consider an online shopping application. The user journey may include steps like “Browse items,” “Add to cart,” “Checkout,” and “Receive confirmation.” Under “Browse items,” stories might include “Search by keyword” and “Filter by category.” Under “Checkout,” stories might include “Enter shipping details” and “Select payment option.” Seeing the journey visually ensures that no critical step is overlooked and that the backlog stays aligned with user needs.

Benefits of Refinement Techniques

These techniques make the backlog more effective and predictable. Workshops build collaboration and shared understanding. Story splitting makes large stories achievable within a sprint. Story mapping keeps the backlog tied to the user journey and business value. Together, they reduce uncertainty and improve the flow of work from idea to delivery.

Conclusion

Backlog refinement is about keeping the backlog clear, prioritized, and actionable. Workshops, story splitting, and story mapping are powerful techniques that help Agile teams prepare for successful sprints. By applying these practices regularly, teams stay aligned with stakeholders, adapt to change, and ensure that each sprint delivers meaningful value.

7.10 Team Agreements – Definition of Ready and Definition of Done

Introduction to Team Agreements

Agile teams rely on shared agreements to ensure consistency and quality. Two of the most important agreements are the Definition of Ready and the Definition of Done. They provide guardrails for when work can start and when it is complete. Without these agreements, teams risk misunderstanding requirements or delivering incomplete work.

Definition of Ready

The Definition of Ready, often called DoR, describes the conditions a backlog item must meet before the team can bring it into a sprint. If a story is not ready, it should not be committed. Typical conditions might include:

- the story is clearly written

- acceptance criteria are defined

- it is small enough to fit within a sprint

DoR prevents wasted time during sprint planning and helps teams start with confidence.

Example of Definition of Ready

For example, a team might agree that a user story is ready if:

- it has a clear description

- it has at least three acceptance criteria

- it has been estimated by the team

- no external dependencies block it

This checklist ensures that the story can be developed without delays or guesswork.

Definition of Done

The Definition of Done, or DoD, is a shared agreement about when work is truly complete. It goes beyond just writing code. A typical DoD might include:

- code written

- peer reviewed

- tested

- documented

- integrated into the system

It ensures that the increment at the end of each sprint is potentially shippable. Without a strong DoD, teams risk building incomplete or low-quality features.

Example of Definition of Done

Imagine a team working on a mobile app. Their DoD might include:

- unit tests passed

- user interface tested on two devices

- security checks completed

- product owner acceptance

By following this agreement, the team knows that every story meets a consistent quality standard.

How DoR and DoD Work Together

The Definition of Ready and Definition of Done complement each other. DoR ensures that stories are prepared before development starts. DoD ensures that stories meet quality standards before they are marked complete. Together, they reduce ambiguity, prevent rework, and promote a steady flow of value.

Benefits of Team Agreements

These agreements create alignment across the team. They build trust with stakeholders because quality is visible and consistent. They also make retrospectives more effective, since the team can measure performance against clear standards. Most importantly, they empower the team to own their process instead of relying on external managers.

Conclusion

Definitions of Ready and Done are more than checklists. They are shared agreements that help Agile teams deliver high-quality work predictably. By clarifying when work can begin and when it is complete, teams reduce misunderstandings, improve quality, and build trust. These agreements are simple but powerful tools for continuous success in Agile projects.

7.11 Using AI to Support Backlog and Requirements Management

Introduction to AI in Backlog Management

Artificial Intelligence can help teams generate ideas, structure work, and check quality without replacing human judgment. By using simple, targeted prompts, AI can support product owners and developers in managing the backlog more efficiently. This covers specific prompts that demonstrate how AI can be used for prioritization, backlog hierarchy, story writing, acceptance criteria, and splitting large stories. Download prompts from the book download materials.

Using AI with MoSCoW Prioritization

The MoSCoW technique is a simple way to group items as Must Have, Should Have, Could Have, or Won’t Have. With AI, you can use the prompt: “Prioritize these backlog items using the MoSCoW technique: [list items].” The AI will quickly sort your backlog into categories. This saves time in workshops and helps the team focus on what is most essential first.

Using AI with WSJF Prioritization

For a more analytical approach, you can apply Weighted Shortest Job First, or WSJF. The prompt is: “Apply WSJF to this backlog: [items with value and effort]. Show calculations and ranking.” The AI will calculate scores and return a ranked list. This allows the team to see which items deliver the highest value in the shortest time.

Breaking Down Backlog Hierarchy

AI can also help transform high-level ideas into actionable work. A useful prompt is: “Given this capability: [insert capability], break it down into features and user stories.” The AI will produce a breakdown that helps the team connect strategic goals to deliverable items. This accelerates backlog refinement and ensures nothing is missed.

Writing User Stories

User stories are central to Agile, and AI can speed up drafting them. A practical prompt is: “Write three user stories for a mobile food delivery app using the format: As a [user], I want [goal], so that [reason].” The AI will generate stories in the correct format, giving the team a head start on backlog refinement.

Improving User Stories

AI can also help improve poorly written stories. You might ask: “Critique this story: ‘Build payment system.’ Rewrite it in proper user story format.” The AI will explain what is missing and rewrite the story to show user role, goal, and reason. This makes vague backlog items clearer and more valuable.

Writing Acceptance Criteria

Once a story is clear, the next step is defining acceptance criteria. AI can assist with the prompt: “Write acceptance criteria for this story: ‘As a shopper, I want to save items in a wishlist, so that I can purchase later.’” The AI will return testable conditions that show exactly when the story is done.

Converting to Given-When-Then

Acceptance criteria become even more useful when structured for testing. The prompt: “Convert these acceptance criteria into Given-When-Then format: [criteria]” ensures that conditions are written as scenarios. This makes them easier for developers to implement and for testers to validate.

Splitting Large User Stories

Large stories are common in backlogs and need to be split into smaller pieces. The prompt: “Take this large user story: [insert story]. Split it into smaller stories using at least two patterns” allows AI to suggest practical ways of breaking them down. It may split by workflow steps, by user roles, or by business rules, ensuring that each smaller story still delivers value.

Conclusion

AI can support backlog management at every step: prioritization, hierarchy, story writing, acceptance criteria, and splitting. The prompts we explored demonstrate how AI provides structure, speed, and clarity. The product owner and team still make the decisions, but AI accelerates the process and reduces the chance of missing important details. Used wisely, AI becomes a partner in delivering customer value faster.

Agile Project Management & Scrum — With AI

Ship value sooner, cut busywork, and lead with confidence. Whether you’re new to Agile or scaling multiple teams, this course gives you a practical system to plan smarter, execute faster, and keep stakeholders aligned.

This isn’t theory—it’s a hands-on playbook for modern delivery. You’ll master Scrum roles, events, and artifacts; turn vision into a living roadmap; and use AI to refine backlogs, write clear user stories and acceptance criteria, forecast with velocity, and automate status updates and reports.

You’ll learn estimation, capacity and release planning, quality and risk management (including risk burndown), and Agile-friendly EVM—plus how to scale with Scrum of Scrums, LeSS, SAFe, and more. Downloadable templates and ready-to-use GPT prompts help you apply everything immediately.

Learn proven patterns from real projects and adopt workflows that reduce meetings, improve visibility, and boost throughput. Ready to level up your delivery and lead in the AI era? Enroll now and start building smarter sprints.

Stop Managing Admin. Start Leading the Future!

HK School of Management helps you master AI-Prompt Engineering to automate chaos and drive strategic value. Move beyond status reports and risk logs by turning AI into your most capable assistant. Learn the core elements of prompt engineering to save hours every week and focus on high-value leadership. For the price of lunch, you get practical frameworks to future-proof your career and solve the blank page problem immediately. Backed by a 30-day money-back guarantee-zero risk, real impact.

Enroll Now HKSM

HKSM